Review by Dennis Ray

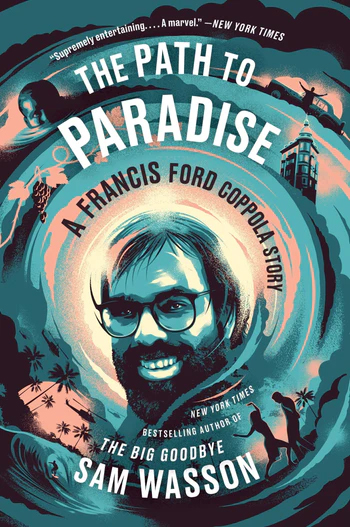

Sam Wasson’s The Path to Paradise is certainly one of the best biographies I’ve read in the past two to three decades due to its depth, structure, and thoroughness of its subject, Francis Ford Coppola’s complex genius. Wasson’s nonlinear storytelling mirrors the unpredictability and ambition of his subject, weaving together Coppola’s personal struggles, creative triumphs, and the broader evolution of cinema with remarkable clarity.

In a single decade, Francis Ford Coppola achieved an unparalleled feat by directing four of the most influential and revered films in cinematic history: The Godfather (1972), The Conversation (1974), The Godfather Part II (1974), and Apocalypse Now (1979). Each of these masterpieces earned a place in the American Film Institute’s Top 100 Movies list, with The Godfather ranked at number 2, The Godfather Part II at number 32, Apocalypse Now at number 30, and The Conversation receiving critical acclaim, though it is not listed in the top 100.

Coppola won the Academy Award for Best Director twice for The Godfather Part II and Apocalypse Now, while The Conversation and Apocalypse Now garnered numerous accolades, including the Palme d’Or at Cannes for both films. Yet, despite this extraordinary success, each project was fraught with challenges. Studio executives doubted Coppola at every turn, often questioning his creative choices and the viability of his vision. Against all odds, he not only made film history but also redefined the boundaries of storytelling and artistic ambition in cinema.

Sam Wasson’s The Path to Paradise: A Francis Ford Coppola Story is a nonlinear biography that digs deeply into Coppola’s early life, his strained relationships with his parents, and his relentless pursuit to please his narcissistic father, who remained impossible to satisfy. This drive culminated in near-psychological collapse during the filming of Apocalypse Now, where Coppola saw himself as the protagonist and his father as the antagonist, Colonel Kurtz.

Like his other works such as Improv Nation: How We Made a Great American Art (2017) and The Big Goodbye: Chinatown and the Last Years of Hollywood (2020), Wasson doesn’t focus entirely on a single subject or idea. Rather, The Path to Paradise intersperses Coppola’s involvement with Hollywood, his connection to the changing times of American cinema, and the importance of Coppola’s influence on popular culture, the modern blockbuster movie, and 1970s cinema as a whole.

Without Coppola, George Lucas might never have made American Graffiti, let alone Star Wars. Lucas may have pursued a comfortable life working with cars or racing. Harrison Ford might never have broken into film, and if he had, it would not have been to the level he achieved in Lucas’s and Coppola’s highly successful films.

The Path to Paradise beginning

The Path to Paradise begins with Coppola of today working on his latest film Megalopolis (2024), starring Adam Driver, Nathalie Emmanuel, Forest Whitaker, Laurence Fishburne, and Jon Voight, mentioning how he sold part of his wine business to help finance the $100 million budget for a film that many believed would never make a profit (and as of 2024, they may be correct).

But as Wasson further explores, Coppola was never in it for the money. He went broke multiple times, took huge risks—some of which paid off and others that nearly got him blacklisted from Hollywood. From here, Wasson shifts to Coppola working on Apocalypse Now, then to Coppola’s youth as a shy, not conventionally attractive, but highly driven youngster pursuing his dreams in filmmaking.

Attending Great Neck High School on Long Island, New York, Coppola discovered live theater and quickly began directing and producing some of the school’s most attended plays, which also had the pleasant effect of gaining him attention from girls. From there, the book moves back and forth from Apocalypse Now to his early career until both narratives converge,pushing onward through the 1980s and 1990s.

Wasson explores Coppola’s success and his role in advancing the concept of the director as auteur. This vision not only produced great movies but also enormous successes, including films like Roman Polanski’s Chinatown (1974), Miloš Forman’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975), and Michael Cimino’s The Deer Hunter (1978).

In 1969, Coppola established American Zoetrope, a San Francisco-based production company that became a haven for filmmakers seeking independence from the constraints of the traditional studio system, directly paving the way for the rise of independent films in the 1980s. Wasson delves deeply into how American Zoetrope emphasized the director’s vision as the centerpiece of filmmaking, paving the way for the auteur-driven approach that characterized the New Hollywood era.

Later, it played a crucial role in introducing digital editing and sound techniques to the industry, reshaping how films were made and presented. In the 1970s, Coppola predicted that films would eventually go digital, allowing filmmakers to beam their movies around the world rather than rely on the costly process of making film reels.

He also believed that theaters needed to update their sound systems to ensure audiences in Indiana could experience Apocalypse Now with the same quality as those attending the LA premiere. American Zoetrope, Wasson aptly notes, derives its name from Greek roots meaning life and turning, encapsulating Coppola’s vision of cinema as a dynamic and transformative force.

Apocalypse Now, Coppola’s ambitious adaptation of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, set against the backdrop of the Vietnam War, is meticulously detailed by Wasson. The myriad obstacles faced during production included severe weather conditions in the Philippines, budget overruns, and the psychological toll on the cast and crew, including Martin Sheen’s heart attack and Marlon Brando’s eccentricities, which Coppola used to the film’s advantage. These challenges mirrored the chaos and moral ambiguity of the war itself, with Coppola famously stating, “We had access to too much money, too much equipment, and little by little, we went insane.”

Wasson also examines Coppola’s complex relationships with collaborators and family members. The partnership with George Lucas is portrayed as a study in contrasts, with Lucas’s pragmatic approach to filmmaking diverging from Coppola’s more idealistic and risk-taking nature. The book delves into Coppola’s familial ties, particularly the integral role of his wife, Eleanor, whose documentary Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker’s Apocalypse provides an intimate look into the Apocalypse Now production, and the highly criticized miscasting of his daughter, Sofia Coppola, in The Godfather Part III (1990).

An interesting aspect of the book is its exploration of how far back Coppola’s later works were first introduced, such as Apocalypse Now, which was initially conceived as a project for George Lucas to direct, in the late 1960s. Another example is Coppola’s admiration for the inventor Preston Tucker, which culminated in the biographical film Tucker: The Man and His Dream (1988) was something Coppola first wanted Zoetrope to produce in the early 1970s.

This film reflected Coppola’s recurring theme of the small visionary battling against the forces of big business, a motif that resonated with his own struggles as an independent filmmaker, and in a way is a running theme through Wasson’s books.

Wasson concludes that to accomplish something truly important, it must be done differently and done better. Both are extremely difficult to achieve. Yet, as Wasson illustrates, those who succeed in their dreams make the world a little better, a little easier to understand, and manage to change it in ways that resonate for generations.